DISCORD Series Artist’s Statement - 2020

The DISCORD (previously referred to as “Imitation of Life”) Series developed from physical and emotional adaptations requiring multiple periods of prescribed bed rest. As an artist, I became disenfranchised from my creative impulses, as well as set apart from the healing act of art making. The walls loomed large overhead and I felt diminished and ill at ease, separate from my own autonomy. What remained of me when ARTIST was removed?

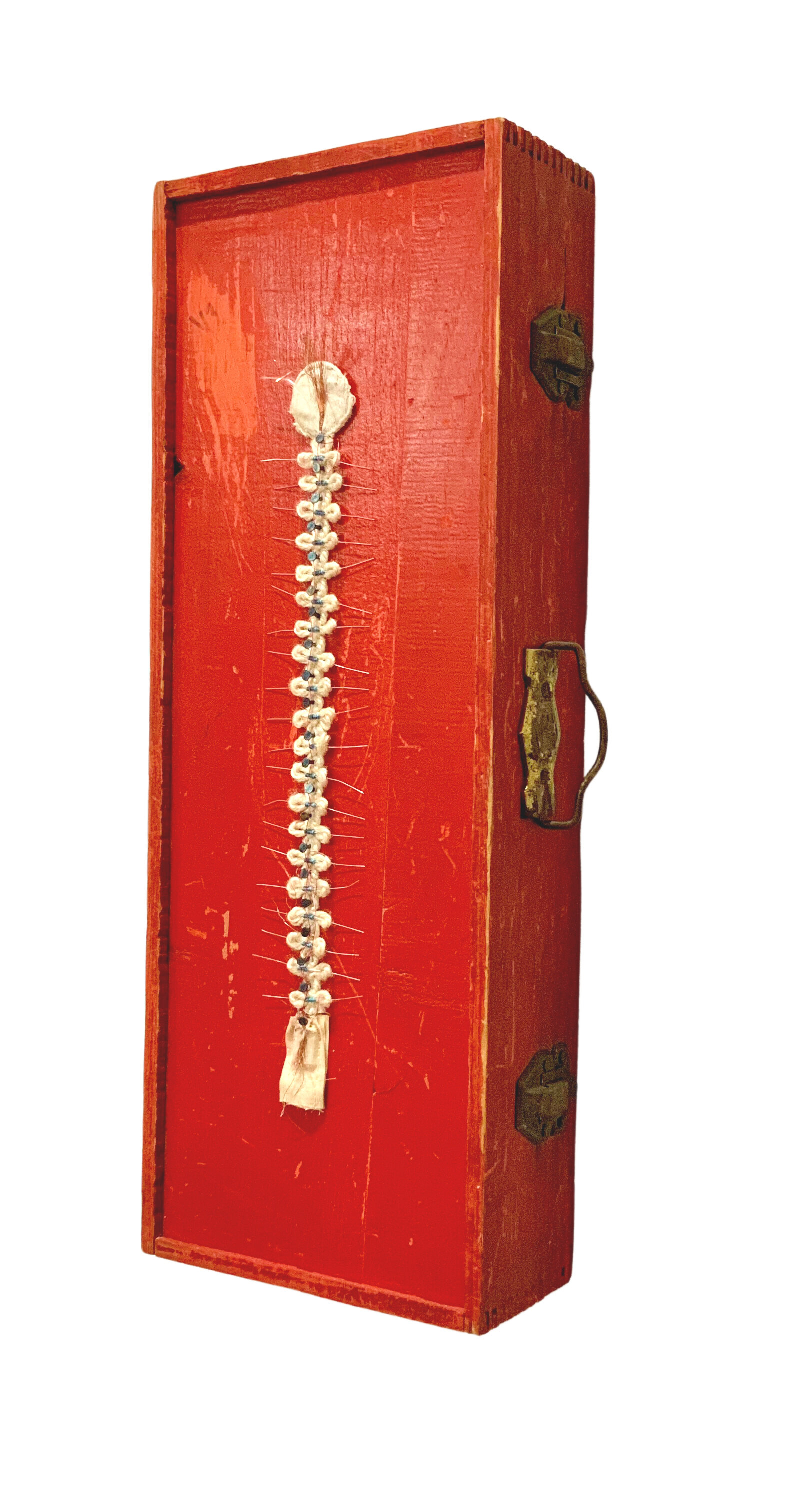

Agitation, 2020

Mixed Media Assemblage 20.25”h x 7.5”w x 3.5”d Tatted Cotton, Nails, Conductors, Resistors, Muslin, Magnets & Wire on Wooden Toolbox

Referencing Spinal Cord Injury, Surgeries & Bed Rest

During the periods of bed rest (totaling approximately 30 months evidenced in the number of doll house beds), I began filling time with ‘home arts’: crochet, knitting, hand quilting and embroidery. I enjoyed this ‘busy’ work, but it did not fulfill my artistic urges. In addition to the physical pain from a fall down my studio stairs in 2009, I suffered psychological trauma with overwhelming feelings of isolation, despondency, worthlessness, anxiety and thoughts of self-harm. The periods of bed rest exacerbated an already stressed psyche. By removing my main coping mechanism (art making), my issues of depression magnified. It was impossible to work in my field of encaustic or sculpture while bedridden, so I recorded ideas in dozens of sketchbooks for future reference. I researched the subject matters and gathered all the supplies needed to create new work, hoping to have what I required on hand when I was physically ‘able’ to create again. I was allowed 20 minutes per hour out of bed, but could barely walk. During those times, I didn’t recognize myself and retreated further into dark rooms, figuratively and literally. My 1,200 square foot custom studio, the very reason we had purchased our new home in 2008, sat abandoned and as forlorn as I was psychologically. I felt very guilty about the ‘wasted’ time, money and space. I didn’t know when or if I would ever salvage my art career and the required bed rest made planning and committing to exhibitions frustrating and impossible. I continually re-injured myself, not knowing exactly what was “overdoing it” or what activities would cause permanent damage versus just causing discomfort.

Artist On Bed Rest

Vintage Doll Bed, Bespoke Mattress, Vacuum Tubes, Monofilament. Assemblage, 2020

Several times in the past decade I attempted to create artworks from the recorded inspirations in those sketchbooks. I even managed to create a few pieces sporadically and exhibited several, but it felt like I was trying to breathe life into dead corpses. I could never ‘catch up’ to the ideas or make enough pieces from each idea to create a full series. Forcing myself to return to the unrealized themes was putting my creative soul and emotional health in jeopardy. My existence was in direct DISCORD with my soul. Much like a mother of miscarried or stillborn children, I needed to mourn the undeveloped possibilities and let them go. On many of those dark days, I considered completely ‘quitting art’ altogether. I felt quitting might be the kindest thing I could do for myself and my family, and it would have been much easier to cease and desist, not to mention, less painful, than to continue agonizing over the false starts and forced stops. My physical stamina never met the breadth of ideas I wanted to visually explore and I finally confronted the fact that many of the works will exist only as ideas . . . they are not meant to be, their ‘time’ has passed. So, I shelved the plethora of sketchbooks and donated dozens of crates of unused art supplies and found objects to Goodwill and to Turnip Green Creative Reuse/Nashville.

Creating DEGENERATE Assemblage #sherfickartstudio

After enduring three (3) spinal surgeries, including the implant of a spinal cord stimulator (a battery unit in my low back with fiber optic leads woven up my entire spine and anchored to my brain stem for the purpose of decreasing/interrupting pain messages sent from my injured spinal cord to my brain), the successive periods of bed rest, in addition to continued long hours hooked up to a ‘charger’, I finally began to explore exactly what type of art I was physically ABLE to create. I decided to process what remained - of myself, of my self-defined creative soul, of the objects that were currently speaking to me. I began researching the spine and what pain does to the body and soul - testing what art making options were left to me within the boundaries of my physical limits.

Many of the objects used in DISCORD reference the mechanical apparatus of my implant, such as: glass/metal fuses (some of which have been ‘blown’), resistors, electrical conductors and elements, diodes, fiber optic and other found wires. The shape of the sculptures (many are on wooden boxes), the found objects (beds and electrical components), and the vertical textiles (hand tatting, lace, upholstery trim) reinforce the form of the spine, its column and parts, and the mechanics of surgery. I used actual hospital gowns to evoke the feelings of exposure and discomfort all patients suffer during their vulnerable admissions. By creating a straightjacket and including the awkward straps, loops, and snaps of the institutional gowns, I re-created my own vulnerability and exhibit both the psychological and physical constraints of being injured. The titles in DISCORD hold double meanings of medical terminology and the psychological effects of pain.

A look at my DISCORD series sketch book and some of the items salvaged from my stepfather’s TV Repair Shop

This series is the reclamation of my creative side. It is a declaration that while “art imitates life”, certainly for the past decade, I have felt my life was a pale imitation of what I was meant to be. It is enough that I survived hundreds of dark and long 24-hour days. Moving forward, I require additional surgeries (with more bed rest), but I hope I have learned better ways to cope with both the pain and isolation that goes hand-in-hand with injuries and chronic suffering. I know I have discovered and developed individual art methods that allow me to create within the confines of my injured body.

Distraction, 2020

Antique Doll Cradle, Tatting, Obsolete Electrical, Iron Tacks

Referencing Spinal Cord Injury, Surgeries, & Chronic Pain with Bed Rest

In fact, I have found new ways to create IN SPITE OF and IN LIGHT OF the pain. After my solo exhibition was taken down in March of 2020, I continued working in this vein and created my ‘covid cabinet’, see below. It is currently on display at The Curb Center at Vanderbilt University in their Art of Healing Exposition (co-sponsored by The World Health Organization.

Post Script, January, 2022

Pain Portraits - created during Year One of the Global COVID-19 Pandemic #sherfickart #painportraits #artofhealingexposition, 2020